Difference Between Newspaper Ad Picture From the Past

Stephen is an advertising representative for a popular business publication. He has worked in print advertising for more than 20 years.

If you think modern advertisements are wild, wait till you get a load of these.

Rishabh Sharma

Newspapers and Advertising

Newspaper advertising has been around almost as long as newspapers themselves. While the first newspapers relied on political patronage, either from a monarch or other governing body, modern newspapers, from the 17th century on, have relied on advertising revenue to keep them in business.

And just as newspapers have evolved over the past three centuries, so has the advertising in them. Though advances in graphics technology have changed the appearance of newspaper advertisements, it is mostly government regulation and changes in societal norms that have changed the content of ads.

Advertising has been a part of our culture since the development of printing nearly 600 years ago, but it wasn't until the mid-20th century that governments began to regulate it for the protection of the consumer. The Federal Trade Commission in the United States was founded in 1914, but it was years before they expanded their mandate to include truth in advertising. Ad Standards, Canada's advertising regulatory body wasn't created until 1957, and the Advertising Standards Authority in the UK didn't come into existence until 1962.

Prior to government regulations, advertising included whatever advertisers felt they could get away with, from wild claims of the healing properties of so-called medicines and the health benefits of smoking to stereotype gender roles and the promotion of Victorian ideas of feminine frailty. If it could help sell a product, it was fair game.

Presented here are 10 old newspaper ads that are so far from what is now acceptable—either legally, socially, or both—that it is difficult to believe they were real.

1. Smoking in Bed

There is so much going on in this simple ad from the Evening Telegram of December 1, 1899, that it is hard to get one's mind around it. Yes, it is an ad for a tobacco product. Tobacco advertising has been banned in most countries for years, but to those of us old enough to remember the Marlboro man and sporting events sponsored by cigarette companies, this is not a big shock.

The amazing part of this ad is that the man is smoking in bed and has fallen asleep doing so. Not only does it appear that the manufacturer of Big Bass pipe tobacco is ok with this; they actually condone it. It seems their only concern here is that the man's pipe has gone out, and they actually command in bold letters that he "Wake Up," apparently for the purpose of relighting it.

". . . for club, family, and medicinal use"

Library of Congress

2. Can I Get a Prescription for That?

There's nothing strange about this ad for Hunter Baltimore Rye from the March 16, 1898, issue of The Sun; we see ads for alcohol all the time. Even the claim that it is the best whiskey in American is not unusual, as this kind of claim is subjective and therefore acceptable in today's advertising.

However, things start to go off the rails when we see that it is recommended ". . . family and medicinal use," that it is endorsed by "leading physicians," and recommended as a stimulant for ladies obliged to use one. There is only one thing to say here: "Can I get a prescription for that?"

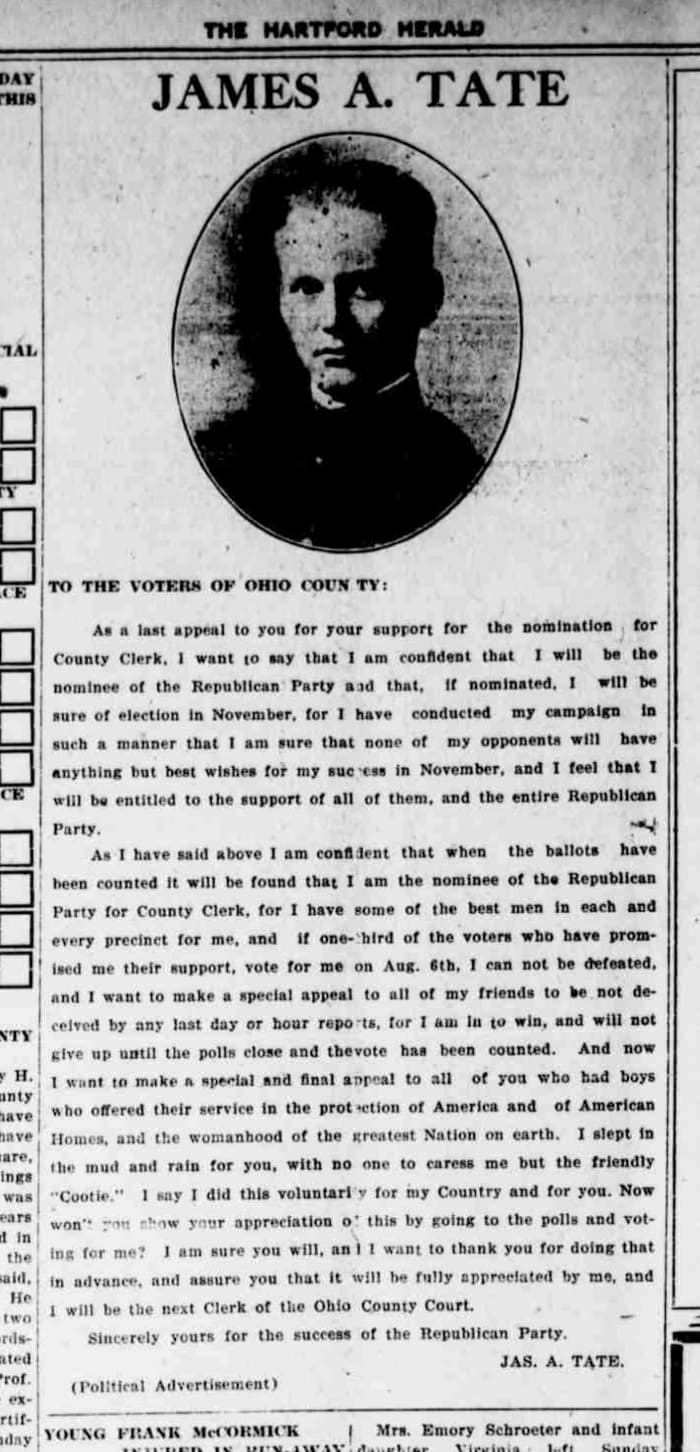

"To the voters of Ohio county . . ."

Library of Congress

3. I Want Your Vote

James A. Tate is certainly not lacking in confidence as he assures voters in this political ad from the Hartford Herald, August 3, 1921, that even his opponents have nothing but the "best wishes for my success in November." As odd as it may seem to us to see a person appeal to voters in this way, it is interesting to note that candidates seeking office once did so by selling themselves on their own merits (though it seems some claims here may be slightly exaggerated) as apposed to bashing one's opponents, as is the case today.

I do not know if Mr. Tate was actually elected to the position of Clerk of the Ohio County Court in 1921 or not. Perhaps a reader from this county with knowledge of Mr. Tate can answer this question and post it in the comments section below.

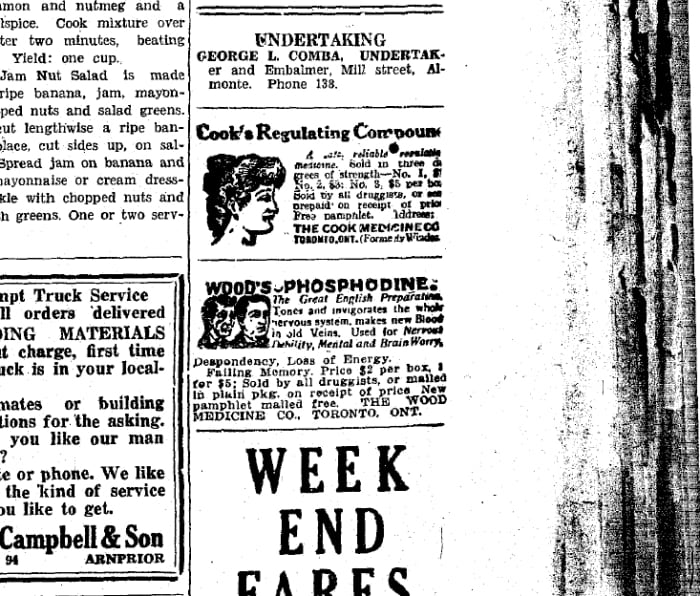

". . . makes new blood in old veins"

BGSU University Libraries

4. If the Cures Don't Work . . .

These three ads are from the Almonte Gazette, January 4, 1940. The first is for George L. Comba, Undertaker. There is nothing odd about an ad for undertaking, though today, the ads are for funeral services, with funeral directors—not undertakers—and though embalmers are part of the process, they are never mentioned in the advertising.

The second is for Cook's Regulating Compound. Again, nothing odd here. We still see plenty of ads for products to keep one regular, though the three different strengths—with an incremental increase in price for each incremental increase in strength—are a little unusual. However, unlike the smiling, happy faces you see in today's laxative ads the woman in this advertisement, even though just a sketch, actually looks constipated.

Read More From Toughnickel

It is the third ad here, however, that should really raise some eyebrows—Wood's Phosphodine. This product actually claims to create new blood, among other things, and the accompanying picture leads one to believe that this miracle drug from the Wood Medicine Company of Toronto can restore one from an aged Abe Lincoln with a serious hangover to a healthy and vibrant young man. As odd as this may seem to us today, it is likely that quite a few people shelled out the $2 per box for this supposed cure-all back in 1940.

At any rate, if the Cook's Regulating Compound and the Wood's Phosphodine didn't work, there was always George L. Comba.

5. A Cure for What?

It is unclear in this ad from the Evening Telegram, December 1, 1899, if the alcohol, morphine, and cocaine is being sold here as "a home cure" for something—or perhaps everything—or if what is being sold is a home cure for addiction to alcohol, morphine, and cocaine. Either way, we can be fairly certain that it did not work.

6. A 10-Minute Cure for Blindness

Again, from the Evening Telegram, December 1, 1899: One newspaper; so many miracle cures. It is hard to say what is most bizarre about this ad. Is it that this woman was suffering from a strange form of blindness that allowed her to see someone's eyes but not their nose? That this blindness was somehow caused by dyspepsia? or that one Ripans Tabule (whatever a tabule is) could cure it in 10 minutes?

7. Ladies Just Fifty Cents

From the Evening Telegram, December 24, 1925, comes this ad for a card party, supper, and dance, with a gender-based admission price. Perhaps it was because the event was held by the Star of the Sea Ladies' Association that the price of admission was $.25 cheaper for ladies than gentlemen. Though $.75 for all of this still seems like quite a bargain, especially with the opportunity to win a $5 gold piece thrown in.

8. You'd Better Watch Out

Again from the Evening Telegram, December 24, 1925: This classified is actually a personal ad—as opposed to a commercial advertisement—but is included here because it demonstrates that even personal ads were pretty much unregulated at that time, and it is also too funny not to include. It is unlikely that a newspaper today would publish an ad that includes a direct threat to another person, though "he will get a fright" is more than a little ambiguous.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, an expressman was a delivery person or any person whose job included the packaging and delivery of any cargo. Apparently, while in the performance of his job, a delivery person damaged the fence in front of S. G. Collier's home and left the scene. Mr. Collier obviously believed that threatening this delivery person with "getting a fright" would result in the man returning and repairing the fence. It would be interesting to know how this worked out.

9. You Put This Where?

From The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 11, 1900—there is nothing to say here; this ad speaks for itself.

" . . . and the patient is not depleted while treating."

Library of Congress

10. False Advertising at its Worst

This ad from Bristol News, March 31, 1874, is an example of the very worst of false advertising. One can only imagine the pain and heartache this charlatan caused people, giving false hope to sick, dying, desperate individuals and their families who paid out good money—money that for many caused great hardship to give up for a cure that did not exist.

This ad appeared in a newspaper at a time when people believed that if it was printed in black and white, it had to be true. It is hard to imagine, even back then, that any newspaper would accept this kind of advertising from an obvious fraud and be complicit in this abominable deception perpetrated on their readers. Nobody should need advertising standards to tell them that this is wrong.

If Proof Were Needed . . .

These are just a few examples of the kind of advertising that appeared in thousands of newspapers around the world prior to the late 20th century. Some are just amusing, some are cause for concern, and others, such as "Cancer Cured," are just despicable.

These don't even scratch the surface of the fraudulent and even dangerous advertising that appeared in print, on radio, on television, and in many other forms before the advent of advertising standards.

If proof were needed that we require regulatory bodies to oversee advertising, one need look no further than a pre-1960s newspaper.

Difference Between Newspaper Ad Picture From the Past

Source: https://toughnickel.com/industries/10-Old-Newspaper-Advertisements-You-Wont-Believe-Were-Real